A common song, one sung by engineers at any number of maturing companies, is how great things used to be, before so many new hires and layers of bureaucracy ruined all the fun. Those were freer times, they’ll rhapsodize when it was easy to run fast, make an impact, and ship code.

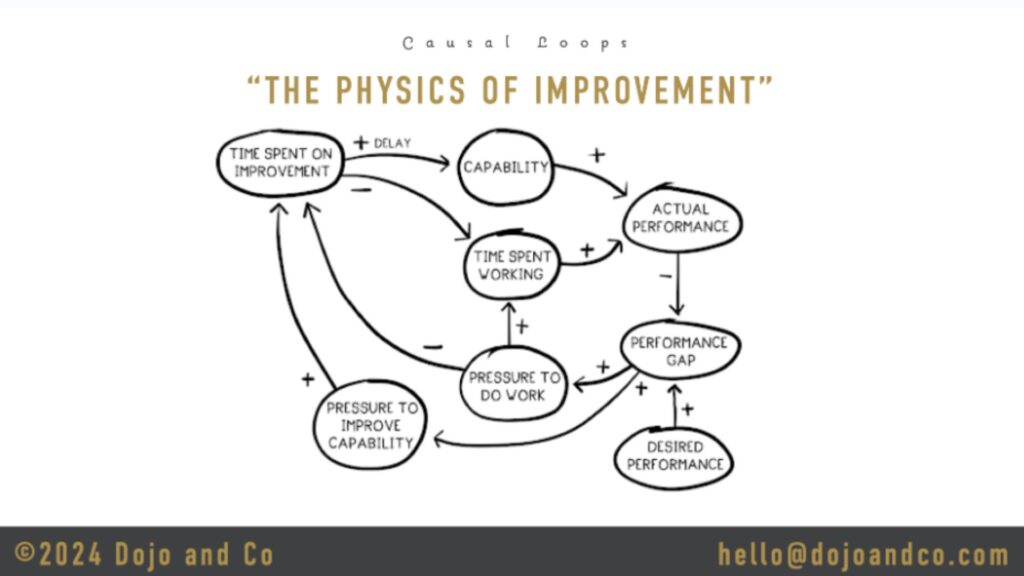

There are several reasons for this growing disenchantment, though one of the most common and costly is the tendency for organizational drag to scale at a rate that outpaces the productivity of new hires. Simply put: doubling a workforce never results in a doubling of output.

Most companies initially organize themselves in a loose federation of teams with their own cultures and coding preferences. When the organization is small and everyone is in close and regular contact, it’s easy to bridge internal differences in a way that enables productivity. However, while new staff are hired at a linear rate (the company now has 200 engineers… now 201… now 202..), the connections and modes of communication between these employees increase at a quadratic rate. Thus, a potential trap awaits; the hard-won success spurring this growth brings with it the potential for “death by 1000 papercuts” as the organization sputters and loses its momentum, taking too long to onboard new hires and limiting the productivity of veterans navigating a shifting ecosystem.

Rarely in engineering culture do people sit down to document the ways and means by which work gets done. Instead, certain select people serve as “supernodes” of information; they are informal yet critical repositories of knowledge to be consulted on why things are and how they came to be. There are countless problems with this approach, one of the most obvious being it’s maddening inefficiency. This oracle spends all of their time answering questions rather than performing their actual responsibilities. Meanwhile, the latency to get a moment of their time and ask a question gets longer and longer, and the work of those waiting to have their questions answered slows.

This is one such “papercut”. Left untreated, it becomes infected. Productivity reduces while dissatisfaction grows. Employees being left to fend for themselves and “figure it out” feel like they’re drowning, while management triages snowballing problems, pulling them away from bringing products to market.

Alex Roetter witnessed this trajectory first hand as he rode the wave of Twitter’s success, starting there in 2010 and eventually moving up to Senior Vice President of Engineering for the entire company. When he first joined, the company consisted of a relatively small number of employees and no revenue. During Alex’s tenure, the engineering team grew to over 2000 and revenue reached $2.5 billion.

However, this extraordinary success didn’t represent the company operating at the highest possible level. For a long time there was, “a culture of everyone doing everything their own way,” he recalls. “Eventually, what became clear is that we were a lot of people not getting enough done for how big we were. No one was asking ourselves if we were getting 2,000 engineers worth of work done every quarter”

This observation led to a key development in Alex’s theory of management, and it’s one that inspires us here at PlusPlus. “You should care about delivering real value for customers as soon as possible,” he says, “and customers are both internal and external. When your team is one person, you can do that with whatever tool you want. When you’re 100 people, the value and consistency of those people working together give you a larger productivity bump than the drawback from people having to learn a new tool or language. A 2000 person engineering team is a massive investment. Customers should benefit and the company should get a large ROI.”

It’s no surprise that companies and teams perform best when all employees are on the same page. Part of good management, then, means giving employees the best possible opportunity to get in sync. They need accessible tools that will enable them to understand the formal systems and informal culture that governs their professional lives.

As established, the exponential growth of organizational drag can sometimes mean that further staffing will create problems at a greater rate than it solves them. A better approach is often thinking about how to increase productivity and better support existing employees. According to Alex, this is often, “the most important thing we can do for morale… for retention, and for our customers.” Not for nothing did Twitter come to have the reputation as one of the best places for engineers to come and do their best work. While increasing productivity sometimes conjures images of humorless taskmasters cracking whips, the right tools actually lead to increased employee satisfaction; they make it easy to, once again, run fast, ship code and make an impact.

Part of the way they accomplish this is via the active participation of employees in defining and codifying the company’s best practices. This isn’t some thankless task, though. We’ve found that it frequently attracts the brightest internal talent. Top engineers want to be involved in this process of codification; they see it as a high leverage opportunity to make their mark and shift the culture. Those engineers might be already existing “rockstars” who want to lead by example, or they may be unheralded yet ambitious talent anxious to prove themselves to the higher-ups. In a market that is ever more competitive, where it’s increasingly difficult to hire and retain talent, the benefits of such a dynamic environment are obvious.

One of our core beliefs is that there exists a fundamental and critical difference between knowledge and understanding. Time and again, we’ve seen companies that have a great wealth of knowledge, but a poor facility in transmitting that knowledge in order to facilitate easy understanding.

We provide that crucial, missing link. Ours is the tool and a methodology that enables that last mile so a company’s culture becomes self-organizing, easily making room for the next person or ten to find a home and add their labor to the effort.

Alex eventually liked PlusPlus enough to become an investor in the company.